Insights and Results

From Our Field Research Partners:

Highlights of AwareComm’s No-Code History

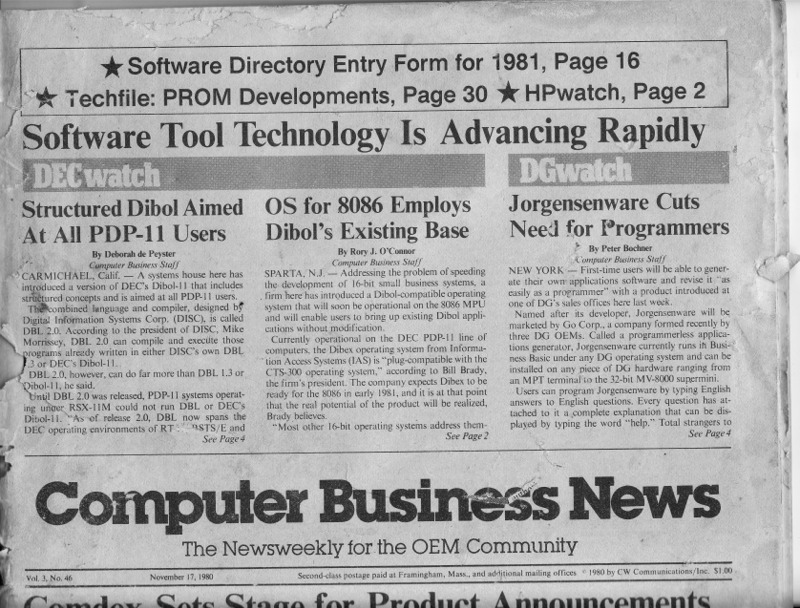

Computer Business News Front Page Headline: “Jorgensenware Cuts Needs for Programmers”

November 17, 1980

By Peter Bochner Computer Business Staff

AwareComm Founder Richard Jorgensen PhD (hc) in addition to being he first OEM for Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and correcting their OS in octal on PDP-8 and PDP-11, he was also the first to create Programmerless Software that created full software application by the Business User on Data General Computers.

Named after its developer, Jorgensenware will be marketed by Go Corp., a company formed recently by three DG OEMs. Called a programmerless application generator, Jorgensenware currently runs in Business Basic under any DG operating system and can be installed on any piece of DG hardware ranging from an MPT terminal to the 32-bit MV-8000 supermini.

This article, originally published on November 17, 1980, highlights the innovative work of Richard Jorgensen, whose development of Jorgensenware to simplify programming for non-experts laid the foundation for his continued contributions at Awareness Communication Technology, LLC (AwareComm.com).

Computer Business News Front Page Headline: “Jorgensenware Cuts Needs for Programmers”

November 17, 1980

By Peter Bochner Computer Business Staff

NEW YORK — First-time users will be able to generate their own applications software and revise it “as easily as a programmer” with a product introduced at one of DG’s sales offices here last week.

Named after its developer, Jorgensenware will be marketed by Go Corp., a company formed recently by three DG OEMs. Called a programmerless application generator, Jorgensenware currently runs in Business Basic under any DG operating system and can be installed on any piece of DG hardware ranging from an MPT terminal to the 32-bit MV-8000 supermini.

Users can program Jorgensenware by typing English answers to English questions. Every question has attached to it a complete explanation that can be displayed by typing the word “help.” Total strangers to computers have been trained to use the software and then written application programs for their businesses with Jorgensenware within one week, according to Bob Smith, one of Go’s founders.

The ease with which Jorgensenware allows the user to change or update his software will also free OEMs from providing the service they must now offer for the software they install. Software has never truly become a product, but has remained a service, according to Steven Brightbill, another founder of go. Because of this, OEM’s cannot mass-market software without a tremendous mass service organization behind them, he said.

“After an OEM has installed 30 to 50 systems, he has a plume behind him,” said Dick Jorgensen, the third founder of Go and the creator of the product. “But instead of a plume of success, it’s a plume of service. And he’s become a service company.”

Software today is either canned or customized. Canned software is inflexible, but even customized software developed for a specific need may end up, afterbody the expenditure of much time and money on the development and debugging process, as a “static software package for a dynamic business,” according to Go. Because no business is immune to change, an OEM, no matter how good it’s software, can expect to be badgered by users for changes, Brightbill said.

With Jorgensenware, however, any user can make these changes himself. Should the U.S. Post Office go over to a nine-digit Zip Code, for example, the cost of converting existing programs geared to a five-digit code will be astronomical, according to Brightbill, because they will have to be recompiled. “There’ll be a whole lot of programming going on,” Brightbill said.

But with Jorgensenware, according to Brightbill, users will be able to expand the space alloted for Zip Codes in their programs in one minute, no matter how large their files are.

The software will enable end users to design their own systems to meet their special requirements and maintain those systems to meet ever-changing needs without resorting to outside assistance. For that reason, Jorgensenware differs from software tools aimed at making programmers more efficient. Such systems are geared to meet the demands of programmers, not the needs of users, according to Jorgensen.

“I’ve seen a zillion programming aids – program generators, code generators, report generators. With all of them, you had to be a programmer to make them work. Now, you don’t have to be a programmer,” said Brightbill, noting Jorgensenware is a programmerless applications generator.

Programmers Hear Death Knell

Does Jorgensenware ring the death knell for programmers? At least one user at a beta test site for the product thinks it does. “I have just written, tested, documented, diagnosed, debugged and run a reasonably complicated inventory control and management program in less than four hours,” he said in a written testimonial. “Programmers, what I have just seen and done will make you obsolete,” the user warned.

If programmers do become obsolete, Jorgensen won’t shed any tears. He feels the creativity they bring to their jobs is an obstacle that prevents software from being truly transferable. That lack of transferability, he noted, limits a systems house’s market.

“We want to chop the creative fingers off programmers,” he said. As software is updated, “each programmer has a need to add to each revision. And how many of them document that revision?” he asked.

Systems Analyst Need Reinforced

However, Smith feels that while Jorgensenware will eliminate the need for programmers, it will reinforce the need for systems analysts.

Go will provide the tools for a user to create a system, but he will still need help defining that system, according to Smith. Part of Go’s charter calls for the founding of a national network of distributors. But in addition to looking for dealers to which to sell its products, the firm will also be searching for dealers from which to buy packages.

Go will then convert other packages in other languages such as Dibol into Jorgensenware and market them for the company nationwide. for the company nationwide. “This will let [OEMs] capitalize on the transferability of their resultant product, which is now truly a national product,” Jorgensen said.

Go feels its product will bring other advantages to OEMs, including exploding the myth that to succeed, a systems house must sell to a vertical market. Smith feels OEMs will now be able to take a limited geographical area and investigate marketing Jorgensenware to professionals in all fields.

“It will be like granting them wishes,” Smith said. He thought an effective technique would be to call a prospective customer and ask him what he needed in a successful applications program. If the OEM can then provide him with that – in a matter of hours — would he be interested in buying it?

Most important for OEMs, Jorgensenware will help revive the flagging margins they have put up with as hardware prices have dropped. To survive, many OEMs have begun to charge for software maintenance. But Brightbill feels this is merely a matter of “borrowing time,” a practice that will catch up to OEMs.

Jorgensenware includes a text editor, but it is also compatible with the word processor, from Satellite Software International. The word processor runs on DG operating systems and costs from $4,500 to $6,500.

OEM reaction to the product unveiling in New York was typified by Robert Beck of CGA, a software company attempting to enter the OEM turnkey market “It looks like what’s needed,” said Beck, who planned to bring several technical people from his company for a closer look at the product the next day.

Go will sell the Jorgensenware concept to OEMs for a $15,000 fee, which Brightbill calls “a license to steal.” The company divides the product into two parts: Build, which enables the end user to write and update his own programs; and Run, a standard set of business applications with a text editor. Each time an OEM sells Build to an end user, he pays Go $5,000; each time he sells Run, he pays $3,500.

Go will be based in Los Angeles, but for now, the principals can be reached at their current companies: Brightbill at Brightcore, Ltd. in Syracuse, N.Y., (315) 685-8653; Smith at Satellite Software, International in Harbor City, Calif., (213) 325-4182; and Jorgensen at Information Management Consultants in Valley Center, Calif., (714) 743-5289.

Computer Business News Front Page Headline: “Jorgensenware Cuts Needs for Programmers”

November 17, 1980

By Peter Bochner Computer Business Staff

page 4

January 1974

Brewers Digest Magazine

page 34

Maximizing Distribution Management in the Brewery Industry (Part III)

“Installing a Data Processing System”

By Richard Jorgensen and Robert Ingram

In the November issue of “Brewers Digest,” we discussed the system requirements for the beverage industry in terms of controls, equipment performance, cost and obsolescence. It was pointed out that under the area of accounting controls, significant emphasis must be directed toward physical handling and rehandling, credit controls, inventory turn and sales reporting. Within the area of equipment performance, we discussed comparison between on-line and in-house systems. Costs and obsolescence were evaluated in terms of both under- and over- automation for a beverage distributor.

No system can be effective for a beverage distributor, regardless of the system’s capabilities in terms of either hardware or software, unless it can be installed at a specific distributor’s place of business in the manner that does not disrupt his current way of doing business. For many who have attempted to implement a data processing system, EDP has come to represent ‘excuses, delays and promises.’ Many distributors after many long months (and often years) of confusion, turmoil, and numerous headaches, find themselves asking …

article text continues below

January 1974

Brewers Digest Magazine

Maximizing Distribution Management in the Brewery Industry (Part III)

“Installing a Data Processing System”

In the November issue of “Brewers Digest,” we discussed the system requirements for the beverage industry in terms of controls, equipment performance, cost and obsolescence. It was pointed out that under the area of accounting controls, significant emphasis must be directed toward physical handling and rehandling, credit controls, inventory turn and sales reporting. Within the area of equipment performance, we discussed comparison between on-line and in-house systems. Costs and obsolescence were evaluated in terms of both under- and over- automation for a beverage distributor.

No system can be effective for a beverage distributor, regardless of the system’s capabilities in terms of either hardware or software, unless it can be installed at a specific distributor’s place of business in the manner that does not disrupt his current way of doing business. For many who have attempted to implement a data processing system, EDP has come to represent ‘excuses, delays and promises.’ Many distributors after many long months (and often years) of confusion, turmoil, and numerous headaches, find themselves asking the question, “if computer systems can control traffic, transmit television pictures from the moon and effectively perform complex modeling functions in a matter of seconds, why then can I not get a simple payroll or an accounts receivable system to function on my machine? What went wrong?” as we examine the distributors who have ultimately reached a successful data processing system within their facilities, as well as those who have failed, we find 3 common areas which create problems.

First, over-automation for the small distributor who is attempting not only to do too much, but attempting to do too much too quickly. It is important to recognize that a change from a manual method of accounting and controls to 1 of automation typically requires patience and understanding of the new tools, all of which involves time.

Second, because an anxious distributor, who has made the decision to automate, either demands or allows premature installation. Most commonly this comes in the form of involving both program development and program check-out in the midst of the installation. The resultant program errors cause chaos requiring more program changes, requiring more check-out, thereby creating an infinite circle of confusion.

The third area perhaps might be classified as training and communication. It has been consistently found that the supplier of the system must have a clear understanding of the distributors problems, from both the standpoint of hardware (the computer itself) and software (the computer programs). If the system supplier lacks a working knowledge of day-to-day operations, the distributor finds himself, at his own expense, educating the technical people. Again, the result is unnecessary confusion and expense to the distributor.

Recognizing these three categories as the most common reasons for data processing failures, we would like to examine the installation of a data processing system in the following terms: First, pre-installation (mandatory steps done prior to the actual delivery and operation of the system); And second, installation which involves program implementation and Technical Support.

Pre-Installation

Pre-installation is perhaps the most important aspect of the installation of a data processing system. During this stage, not only the detailed plans as to how the system will be installed are made, but provisions must be made for the system to be capable of actual parallel operations during this stage. To be effective, the pre-installation encompasses the following basic 7 operations:

1. Current review of all operations as they exist today. Included in this process must be a review of sales processing, truck routing, invoices, sales reporting, truck loading, driver check-in and all current billing procedures.

2. Systems review. Both in-put capabilities, as well as reporting capabilities, of the system must be not only carefully and thoroughly presented to all affected personnel at the customer site, but also an actual demonstration to the operating personnel must be made off-site. This insures that the operator gains confidence in the system while the technical personnel are provided with a clear understanding of the information required for data conversion.

3. Complete database conversion. Under the direction of data processing personnel, the distributor must provide specific information relative to his customer file, billing procedures and inventory. The data processing supplier will then be able to take this basic information pertaining to the distributors operation and create a complete database on the computer system.

4. Operations training. Having already once been exposed to the capability and the procedures of the system, now the potential operators are brought to the suppliers site for training. Having the database (customer file and inventory information) available on the machine which is ultimately delivered to the distributors facility, the operators must then be given the opportunity to become not only familiar with the policies and procedures of the system, but must develop the confidence that they can operate the system on their own. Once familiarization with the command structure of the system has been attained and the proper confidence level of the operators has been achieved, the potential operating personnel are ready for their fifth step within the pre-installation process.

5. Remote parallel operation. During this phase, a minimum input of one day’s actual information must be made into the system and processed to provide a parallel comparison of the results to the current manual operation. This step is mandatory to insure that no unique and unusual conditions occur in their present system that have not been communicated to the data processing supplier. In addition, it builds further confidence in the operator in terms of her own capabilities and the capabilities of the system. Once the initial remote parallel operation has clearly established that there are no unique conditions that will occur when the system actually begins operating and the operator feels qualified (at least under supervision) to operate the system, the distributor is ready for the final two steps in the pre-installation process.

6. Review of the facilities. This must encompass the evaluation and assignment of proper space to provide necessary work and storage area as well as the testing and measuring of the electrical facilities within the building to insure against potential power problems that could cause unnecessary delays during actual installation of the system. Once this is accomplished, the final step can then be taken in the pre-installation process.

7. The specific assignment of personnel. Specific personnel assignments are required in order to function effectively under the parallel operation for the first month of the installation. Only after the preceding steps of pre-installation have been accomplished should a distributor consider on-site installation of his data processing system.

Installation

The actual installation of a data processing system for a beverage distributor should consist of two phases:

The first phase is the actual delivery of the computer itself and thorough testing and check-out procedure, to ensure that all equipment is performing correctly. Typically, a beverage distributor should allow two to five days for this to be accomplished. Once thoroughly checked out, the computer is then, and only then, ready for operation. It is strongly recommended that the implementation of the various programs can be done carefully and in very specific sequences. The first step is to insure that data can be accurately entered into the system, and that the database originally provided by the distributor is accurate in terms of discount items, prices, account information and customers. This is accomplished by comparing the computer out-put and invoices with the results of the manual operation. If after a minimum of at least one week, item numbers, customer numbers, the customer names and addresses are correct, the distributor is then ready for the second phase, or the driver check-in procedure.

The driver check-in parallel should also continue for a period of at least one week to insure on a consistent basis that all dollar figures, both cash and charge, reconciled to the penny with the manual system. Once this is accomplished, the next step, which is sales reporting, can be taken. This step, as with the previous one, requires that the computer system must balance or be able to reconcile to the manual system. Once the functions of invoicing, driver check-in and sales reporting, in terms of both dollar and quantities, have been proven accurate, the distributor is then ready to fully implement the accounts receivable in-put phase of his installation. The distributors personnel in conjunction with the Technical Support of the supplier, enters opening balances for all his accounts receivable at a given date. From that date on, posting on a daily basis results in the accumulated sales information in conjunction with the received-on-account information. This phase of the operation should continue for a minimum of 30 days. At which time, after comparison of the computer generated statements with those maintained by the manual system, reconciliation must occur. Once this has been accomplished, the distributor is ready for the final stage of automation – that involving his payroll. It is strongly recommended that the same procedures outlined in implementing inventory, accounts receivable and sales reporting system be followed here also.

Throughout this initial period, the beverage distributor installing the computer system must be assured that adequate Technical Support will be provided. Technical assistance is necessary, both in the form of supervisory personnel and of program support. Preferably, this level of support is included in the total price of the system.

In summary, we strongly recommend that if a distributor should choose or make the decision to automate, he establish himself with a firm that provides not only the hardware computer capabilities, but also the software. Included in the hardware/software package should be a proven and established approach to convert the data processing requirements of a distributor into reality within a reasonable time frame. Selecting the data processing supplier on this basis will assured not only the technical qualifications of the firm, but also their specific knowledge of the beverage industry in depth.

January 1974

Brewers Digest Magazine

page 36

Maximizing Distribution Management in the Brewery Industry (Part III)

“Installing a Data Processing System”

By Richard Jorgensen and Robert Ingram